Writers: Robert P. Thompson and Gaylord Dubois

Writers: Robert P. Thompson and Gaylord DuboisArtist: Jesse Marsh

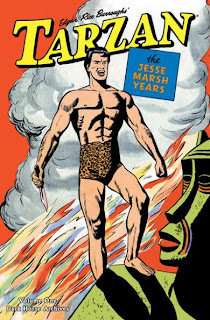

Collects: Dell Four Color Comic #134 & 161, Tarzan #1-4 (Dell Comics, 1947-48)

Published: Dark Horse, 2009; $49.95

Tarzan first appeared in print in the pages of All-Story Magazine in 1912, with author Edgar Rice Burroughs’ novel Tarzan of the Apes following just two years later. The character proved to be so popular that he was already appearing in movies by 1918, which would continue to be released almost yearly through the 1960s. Tarzan made the leap to newspaper strips in 1929, but even then, almost two decades passed before he began starring in his very own original comic book stories, which were published by Dell Comics. Tarzan: The Jesse Marsh Years, Vol. 1 reprints the inaugural issues of Dell’s series, and the book is an extremely welcome addition to the ever-growing number of archival comics collections that a range of companies have been publishing over the last few years.

The reason I begin this review with a recounting of Tarzan’s history in popular culture is that his first comic book series is built heavily on the character’s various representations over the preceding decades. Furthermore, it could easily be argued that the comic draws more from the cinema than it does from its own medium. The plots are well-structured and progress more like short films than typical comic book stories from this period, and at around 40 pages each, they’re fairly long for their time. The dialogue is a bit wooden, but as Mario Hernandez writes in the book’s introduction, it works perfectly for the subject matter. Reading Tarzan, I constantly felt like I was watching an old B-movie or film serial – and I mean that as a compliment. As cheesy as some of those movies were, they were pretty darn entertaining, and they obviously had a pretty lasting effect on popular culture – how many people can you think of who have never heard of Tarzan?

Other cues are taken from the films as well. Most prominently, artist Jesse Marsh draws Tarzan as a hulking, barrel-chested, strikingly handsome man, a nod undoubtedly to Johnny Weissmuller, who was the actor most identified with Tarzan at the time. But a number of aspects are drawn from the books as well, including the character of D’Arnot, a French naval lieutenant who serves as an occasional companion to Tarzan. The writers, Robert P. Thompson and Gaylord Dubois, also make frequent use of words from the ape language invented by Burroughs; they even devote a few pages in each issue to an ongoing “Ape Dictionary,” which features intricately detailed artwork by Marsh.

It’s worth dwelling on Marsh for just another moment – after all, Dark Horse did see fit to put his name in the title of this collection. A veteran of both illustration and animation, Marsh depicts the jungle and its inhabitants with a lush detail that was simply unparalleled at the time. Lions crouch and pounce with sinewy leaps, apes swing from the trees and land into a lumbering gait, and the jungle’s dark foliage exudes an almost overwhelming sense of mystery and foreboding. Truly, the 1940s were a “golden age” not just for masked heroes, but for the portrayal of the strange and exotic in a way that was both fantastic and beautiful.

Although the stories are pretty well-structured for the most part, the one thing that did bother me about them is that Tarzan’s ultimate goal is almost always to save a white person being held captive by jungle savages – often referred to as “Go-Mangani,” or “blackmen.” In fact, at certain points it’s almost as if the character can’t be bothered to do much of anything if it doesn’t involve saving white people. In “Tarzan versus the Black Panther,” for example, Tarzan sets out to save a white woman from a slave trader; freeing the dozen or so black slaves the trader has captured seems to be little more than a secondary goal. It seems a bit peculiar that Tarzan, a man raised in complete isolation from the rest of the human race, seems to draw so many racial distinctions (subconsciously or not) among other human beings.

Still, I do give Tarzan some credit for its sympathetic portrayal of Muviro, Tarzan’s African ally who appears at some point in almost all of his adventures. And in case I’ve been making the comic sound worse than it actually is, I should point out that it’s never overtly or intentionally racist – as “products of their time,” some of the stories are just a bit ignorant. Actually, when you compare it to a good deal of other comics and even animated films that were being released at the same time, Tarzan seems like a regular civil rights manifesto.

Of course, Tarzan’s racial sensitivity, or occasional lack thereof, is more of a reflection on the particular writers of this collection than on the character himself (although Burroughs’ original novel espouses its fair share of troubling notions about race as well). Tarzan is really a lot like Conan or even the Hulk in that sense – his intelligence, as well as the extent of his physical capabilities, vary from story to story depending on how each writer interprets the character. This is no more apparent than in the last few stories in the book, in which Marsh and company change things up in a big way with the introduction of Tarzan’s wife Jane and their son Boy.

In these stories, Tarzan isn’t so much an uncivilized nomad as he is a family man concerned primarily with teaching his son how to survive the dangers of the African jungle. One story even features Boy as the protagonist, with Tarzan showing up as sort of a deus ex machina at the end to save Boy from the clutches of a strange tribe of pygmy warriors. I’m curious to see whether subsequent Tarzan comics from this era will continue to be as experimental in their plotting, or if this was just a one-time attempt to see if a different kind of story would still resonate with young readers.

It would certainly be fair to call Tarzan: The Jesse Marsh Years one of the better archival series being produced right now, and with five volumes already released in less than a year and a half (and a sixth one due next month), it’s clear that Dark Horse is committed to seeing the material through to its end, and in an extremely timely fashion to boot. So much the better for me, since I will certainly be reading the next volume, and possibly more after that – even if it’s more for Marsh’s brilliant artwork than for the stories themselves.

Rating: 3.5 out of 5

Oh wow, how does he get his hair to stay like that?

ReplyDeleteAn excellent question, and one that we probably don't want to know the answer to!

ReplyDeleteThis is another excellent review, Marc. It's like you went to college or something.

ReplyDeleteAs with your last review, I don't have any experience with this specific story. I thought it was interesting that you brought up how people everywhere know of Tarzan, because it's a pop culture truth I never considered. It seems the primal nature of the character and the simplicity of the concept make him pretty accessible.

It's also interesting that you bring up the points about racism. You take a more fair-minded approach to it than most readers probably would. However, I think I'd have to read these stories first-hand to form my own opinion towards those elements.

Have you ever read any of Joe Kubert's Tor? That's the closest thing I've read to a Tarzan type character. In my mind, Ka-zar by Mark waid doesn't count. (Yes! I got my Waid reference in on your blog!)

Thanks, Kello! In regards to the issue of race in this book, as with many other books and movies made during that time, I agree that it's something people should certainly be able to evaluate for themselves. There are a number of Bugs Bunny and Tom & Jerry cartoons (just to name a few examples) that send some people into an uproar for their content, as well they should; but what's even more troubling to me is that Warner Bros. refuses to re-release these cartoons in any way, shape or form.

ReplyDeleteI think it's important that these kinds of things are still made available to people today, if not necessarily for their entertainment value than for their value as artifacts of our cultural history. As long as there are disclaimers about any possibly objectionable content (which there are in the case of this book, to its credit), I don't see what harm can come of allowing people access to this material again.

I haven't read Tor, but I recently came across some interviews Kubert did about the original series, and they were very interesting. Actually, I'm really anxious to read Kubert's work on both Tarzan and Tor after reading this book. My understanding is that the first few of his Tarzan issues serve as a direct adaptation of the first novel, which I'd really like to see. As I mentioned briefly, the original novel itself has some questionable racial content (I read it just a few weeks ago, so it's very fresh in my mind!), so it will be interesting to see how Kubert deals with those. Which Tor series have you read -- the original one, the new one, or both? What did you think of it?

And wow, I had completely forgotten about Mark Waid's Ka-Zar series! Interestingly enough, he did that with Joe Kubert's son Andy (in part, at least), so I guess in a way he was responsible for bringing the whole archetypal jungle-man story full circle for them.

It is pretty cool that Dark Horse put a disclaimer in. That again goes to show the level of commitment to this material that you mentioned, because it means they didn't just reprint it and send it out, but looked at the stories.

ReplyDeleteI very recently read the new Tor series, and while it was verbose and a little dull, I really liked it. I have a ton of respect for Joe Kubert, especially after reading the first few chapters of his biography and seeing where he came from.

And I actually liked that Ka-zar series a lot because of Andy's work. I remember being really jazzed to read it as it came out when I was in 8th grade (because it had two of my favorite creators), and then it got to an issue with a fill-in artist and I completely gave up on it. I'm such a fair-weather Ka-zar fan.

Kello, I think Marvel heard us:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.amazon.com/KaZar-Mark-Waid-Andy-Kubert/dp/078514353X/ref=sr_1_41?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1280242342&sr=1-41