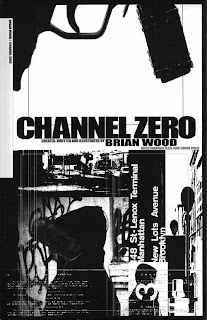

Writer/Artist: Brian Wood

Writer/Artist: Brian WoodCollects: Channel Zero #1-5 (Image, 1998)

Published: AiT/Planet Lar, 2000; $12.95

Before Demo, DMZ, Northlanders, and a handful of other wonderful comics being written today by Brian Wood, there was Channel Zero. If you didn’t know better, though, you might be hard-pressed to pick out Wood’s first graphic novel as having come out so long before what he’s done recently; it fits in that well, stylistically and thematically, with the rest of his body of work. Although he actually created it as part of a final project for graduation from design school, it shows the same depth and polish as his comics today, proving that Wood is an artist whose intimate understanding of his craft extends all the way back to his beginnings.

Channel Zero is set in an alternate near-future in which America is controlled by government corporations and freedom of expression has been all but completely suppressed. The media has been taken over by the government as well, due to Congress’s passage of the “Clean Act.” Wood writes that the law was spearheaded by the extreme right and that most of the population went along with the change, being “either in support of it, or too lazy to do anything about it.”

Enter Jennie 2.5, a young, self-described “uber-geek” whose dream to be an investigative journalist met an early death in the wake of the Clean Act. She’s an angry, rebellious young woman, as evidenced by her heavily tattooed body and penchant for hacking into various government-controlled computer systems. You can think of her as sort of a cross between Aeon Flux and Neo from The Matrix, except without that’s movie’s rampant slow-motion effects or its crash-course approach to college freshman philosophy.

Jennie is one of the few people actively seeking to bring the Clean Act down, and she sets out to do it by broadcasting her own pirate television program. Over the course of the book we see her rise from techno-punk revolutionary to widespread cultural phenomenon, both from her perspective and from the perspectives of everyday people living in New York City. This is actually one area where the book falters a bit, in that it spends a little too much time (in its second half, especially) focusing on the lives of people other than Jennie. One section, for example, tells the story of a “cleaner” whose job is to eliminate people who speak out against the government, even if their crimes are as minor as posting anti-government flyers. While it’s effective in building on the backstory of the world in which Channel Zero takes place, it does fairly little to advance Jennie’s story, which I think is by far the most crucial aspect of the book.

The art has a strong graphic design element to it, which makes sense given Wood’s background – although he worked in comics off and on for a few years around the time of Channel Zero, he was actually a graphic designer first and foremost until 2003. You’ve probably seen a good deal of his pre-comics work without even realizing it; he designed the box art for a number of video games, including Grand Theft Auto III and Max Payne. Elements of that style are definitely apparent in Channel Zero, with its mix of photorealistic and sketch-like art, all in stark black and white.

Wood’s background in design also shines through in the form of fake propaganda posters which frequently intercut the main story, almost like advertisements in a traditional comic book. Taking the propaganda theme even further, Wood often hides the catch-phrases and buzzwords from these posters (e.g., “evolve and revolve,” or “make them understand”) in the artwork of actual story pages, effectively creating mock subliminal messaging. Some parts of the book are even more overt in satirizing the media – for instance, one lengthy scene actually has an ongoing ticker tape running along the bottom of the pages. The end result is a comic that ridicules the media for using certain techniques as tools for social manipulation, even as it reappropriates those very techniques for its own purposes. It’s a neat effect, and one I’ve never seen attempted in this medium before.

As you can probably tell from everything I’ve said about this book so far, Wood’s politics in Channel Zero aren’t exactly subtle. It would have been predictable and easy for him to end the story with Jennie leading the people to some glorious, government-toppling revolution, in which case I think I still could have called this book a good, if not great, first graphic novel. But its ending is actually quite unique, in that it paints a realistic picture of one person’s inability to change society, no matter how popularly known that person is. Jennie isn’t devoid of the same flaws and selfish desires that any other person possesses, nor does she have the power to command social influence by force of will alone.

Wood’s purpose, I think, is to show that in order to oppose a system, one first has to acknowledge its existence; and that in the very act of acknowledging it, one enters into dialogue with and therefore becomes a part of it. In Channel Zero, Jennie does just that. Although she wants to be a “woman of the people,” she also wants to be a celebrity, in her own way, and unfortunately for her it’s impossible to be both in her world. By becoming a part of the “mainstream,” Jennie also becomes a cog in the wheel, another tool to be manipulated by the powers that be. In the very act of rebelling, she has played into the oppressor’s hand.

Some have suggested that Channel Zero is a traditional “government vs. the people” story set in a hyperbolic extension of Giuliani’s New York. If that were the case, the book would be little more than an angry political statement by an up-and-coming comics creator; but it’s more than that. Jennie’s recognition of her failure as a revolutionary and activist seems to represent the author’s own frustrations: Wood clearly yearns for social change, but at the end of the day the best he can do about it is to write and illustrate a comic book story – and aren’t comics themselves just a part of the mass media system that Wood so despises?

Like Jennie 2.5, it would seem that Wood too has become a part of the system. By the same token, though, I think he also shares in her optimism and in her hope for the future – a hope that the next generation will learn from the mistakes and limitations of this one, and that their world will be a better one than ours as a result. And what can we do to ensure that this better world comes into being? If we believe Brian Wood, it all starts with turning off the television.

Rating: 4 out of 5

No comments:

Post a Comment