Writer: Brian Michael Bendis

Artists: Chris Bachalo, Frazer Irving

Collects: Uncanny X-Men #1-5 (2013)

Published: Marvel, 2013; $24.99 (HC), $19.99 (TPB)

Brian Michael Bendis’s Uncanny X-Men exists at a strange remove from All-New X-Men, being at once a companion piece to the writer’s other flagship X-Men title and a series with a coherent raison d’etre of its own. The first collected volume, Uncanny X-Men, Vol. 1: Revolution, focuses on the shambles Cyclops and his cohort (Emma Frost, Magneto, and Magik) find themselves in as they attempt to train a new generation of mutants. (It’s ironic, isn’t it, that Bendis’s “all-new” characters – Tempus, Triage, Fabio, and Benjamin – make their home in Uncanny, while the stars of All-New are the time-displaced “all-old” X-Men of the 1960s?)

Some of the most interesting and best-written moments in Revolution are actually ones previously seen in All-New X-Men, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, presented here with a focus on the character interactions we didn’t see in Bendis’s other X-book. When Cyclops & Friends show up at the Jean Grey School to recruit more mutants to their cause, for example, Bendis overlays the war of words between Cyclops, Wolverine, and Kitty Pryde with a psychic showdown between Emma Frost and her former protégés, the Stepford Cuckoos. The girls feel betrayed by Emma’s apparent loss of her mutant abilities, casting a harsh light on Emma’s own sense of betrayal – one directed at herself on the one hand, but also at Cyclops, both for unintentionally breaking her mutant powers and for breaking her heart as well.

As fascinating as moments like these are in their own right, they also serve as consistent springboards to what gives Uncanny X-Men its own identity in relation to All-New X-Men: the “broken” nature of its cast’s mutant powers in the wake of Avengers vs. X-Men. If All-New is about inexperienced young mutants learning to utilize their talents to their fullest potential, then Uncanny is about experienced older mutants half-conscious of their new limitations but who try to do what they think is right anyway. Throughout Revolution the utter inability of Cyclops and his team becomes increasingly disconcerting, especially considering that half of them are completely untrained. While the team narrowly escapes potentially deadly encounters with Sentinel robots and the Avengers in this volume, it seems only a matter of time before Cyclops’s hubris will result in tragedy. Chris Bachalo’s artwork, fittingly, is as beautiful as it is unsettling, his frequently off-kilter panel layouts creating a near-constant sense of unease and impending danger.

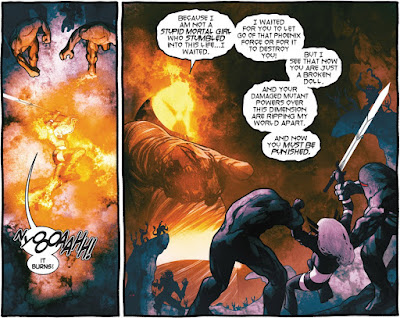

The final issue collected in Revolution features painted artwork by the equally talented Frazer Irving, but unfortunately the story itself – about denizens of the demonic Limbo dimension coming after team member Magik – leaves much to be desired. As longtime readers of this blog might recall, I’ve never been too keen on demons serving as the antagonists of superhero comics (see also: my reviews of Superman: Kryptonite Nevermore, Batman – The Dark Knight: Golden Dawn, and Nightwing, Vol. 1: Traps and Trapezes). At best such stories tend to read essentially as cardboard cut-outs of one another, offering up supernatural excuses for the main character(s) to fight endless hordes of generically ugly bad guys. At worst, though, they legitimize the use of sexually violent language and imagery as a plot device; just consider the number of stories we’ve all read and watched about death-cults sacrificing virginal young women to Satan (or some other demonic entity). Only adding to the unpleasantness is that these types of stories tend to wrap themselves in pseudo-religious mumbo-jumbo, adding yet another dimension of poor taste to the proceedings.

In Revolution we have the worst of all these worlds, with characters threatening to “damn” and “punish” each other and Magik in particular singled out as a “stupid mortal girl,” a “broken doll” who “must be punished.” Magik, for her own part, sprouts horns and hoofs and begins referring to herself as “the Darkchilde.” It’s pretty insufferable stuff. It never gets quite as perverse as some of the character’s earlier appearances – I’m thinking especially of Chris Claremont’s Magik (Illyana and Storm) and the hopefully never-to-be-reprinted Magik miniseries of 2000-2001 – many of which more explicitly evoked pedophilia and rape. But even so, one might hope that this character’s thirty-plus years of publication would be long enough for us to have moved past this brand of storytelling.

Revolution ends right in the middle of this dreadful story, leaving it to drag on for another two issues in the series’ next collected volume. I’ll say more about the story’s conclusion should I get around to writing about that book, but in the meantime it’s worth noting how irritating it is that both this volume and All-New X-Men, Vol. 2: Here to Stay end on cliffhangers. Since characters weave in and out between All-New X-Men and Uncanny X-Men, this makes it impossible to read either series in trade without spoiling the other, even if you switch from one series to the other between individual collections. (And that’s to say nothing of how both series intertwine with Brian Wood’s X-Men, Rick Remender’s Uncanny Avengers and, eventually, Bendis’s Guardians of the Galaxy and Miles Morales: Ultimate Spider-Man.)

In short, while the first four issues collected in Revolution represent some of the strongest work by both Bendis and Bachalo in recent years, the way this volume concludes sends up serious red flags. I’ve mostly enjoyed Bendis’s two X-Men titles so far, and I sincerely hope this isn’t a sign of things to come.